“Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption” is one of the best known works of Stephen King, taking its place as the first story in his collection Different Seasons. Millions of people have fallen in love with this story and Frank Darabont’s adaptation for its touching look at the growing friendship between two convicts who provide each other with the hope of having a better life.

What most readers fail to realize, however, is the question that King explores through his story; is isolating and imprisoning convicts the best way to make them better citizens? In Shawshank, King claims that no, it is not, and uses the novella as an invitation to critique the American penal system, highlighting the emotional and physical abuse inmates face, how these experiences have the ability to create criminals, rather than make them better citizens, and the potential to become severely institutionalized. Darabont, who created the film adaption of the novella, reiterates these ideas by expanding upon certain characters barely mentioned in the novella as well as the scenes that take place throughout King’s story. However, Darabont does not only reiterate King’s message, but he adds to it, claiming that in reality it is all about hope. Hope is what makes a person better.

Right away King introduces readers to the abuse prisoners face when they spend time in prison. By the end of page twelve King is describing the roughed up state of Andy who had a swollen lower lip and right eye and a bad washboard scrape across his cheek. He uses Red to explain that Andy had been abused by the ‘sisters’ who “are to prison society what the rapist is to the society outside the walls.” These men choose to attack and forcefully rape any of the men they can get their hands on and it is nearly always a gang-rape. No man who is incapable of holding his own against one or more of the men in the gang would be raped and have his life threatened if he did not do what he was told to do. Prisoners can fight back, and do, but in the end they merely end up beaten and bloody, sent to the infirmary and spend time in solitary for the fight.

Darabont backs King up portraying the abuse inmates receive from the guards as well. Within the first ten minutes of entering the prison scene, viewers see a guard forcefully hit a prisoner for asking a question. A few minutes later, the other prisoners harass and mentally abuse a new inmate ‘fish’ and when the inmate loses his mind and breaks down, the head guard removes him from his cell and beats him nearly to death. In fact this prisoner does die, over night when the doctor is home. Throughout the entire film examples of abuse by the guards are prevalent; a beating here or there, fowl name calling every time they speak to you, murder, and the warden giving out plenty of time stuck in solitary, more time than any man or woman could handle without suffering from serious psychological problems afterwards.

These instances of physical and mental abuse by both the guards and the other inmates are not something that King and Darabont simply make up for the story they tell. A judge said of Texas prisons that the system is a “culture of sadistic and malicious violence.” Assault and brutality by hand and stun guns as well as batons or other blunt objects is a common occurrence in most prisons in America. In Florida, a man was beaten so badly that every rib was broken, his testicles were swollen, and he had boot marks on his body. He died from the assault and authorizes merely claimed that the injuries were ‘self-inflicted’. This abuse extends to detained youth as well. An incident in Maryland led to criminal assault charges filed against guards at a youth detention center after one guard held a boy while “three other guards kicked him and punched him in the face.” The abuse perpetuated behind the stone walls of America’s prisons is very prevalent, unrestricted, and is accepted and even approved of by many of the authorities within the prison.

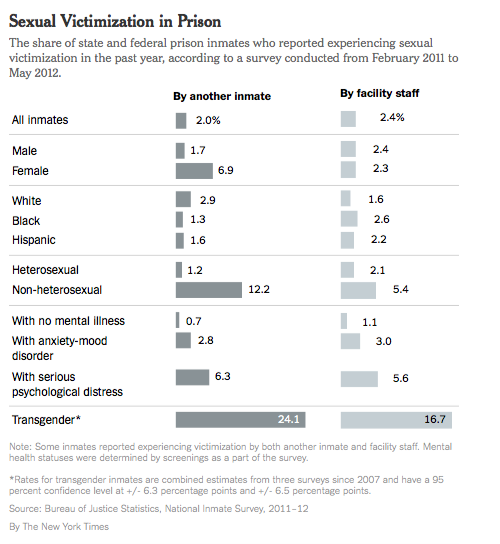

Rape is also an enormous problem, especially for women. However, it is not only coming from the other inmates. Often times the correctional officers, those meant to keep order within the walls, are the ones perpetuating the rape. In fact, studies find that 60% of all cases involve the staff rather than other inmates. The staff members themselves want it or can be bribed into forcing another man or woman into any kind of sexual act. And when an inmate comes to them to ask for protection they are often ignored or laughed at. According to prisonlegalnews.org, “A common thread of rape, debauchery and even sexual torture is present in detention facilities nationwide.” The site also provides several cases from different states where prison staff have been busted for unlawful sexual relations with inmates.

Many of these cases, such as Colorado guard Russell Rollison, who threatened two women and forced them to have sex with him, and that of Steve Edward Hiser who was charged with sexual battery, indecent exposure, oral sodomy, and rape by instrumentation, among others, are not being treated with the gravity with which they should be. In 2006 BJS reported that “77% of staff members involved in substantiated incidents of sexual abuse had resigned or were fired, while only 56% were referred for prosecution.” Of those who do find themselves in legal trouble, the punishments are seldom serious enough to change the way officials are acting.

From the above examples Rollison was heavily charged but by the time his trial was complete, the charges were reduced and he received probation only. When Hiser’s trial had finished his charges had dropped to sexual battery and rape by instrumentation. He was given two ten year suspended sentences and fined only six hundred dollars. There are numerous other accounts of gross sexual abuse by both male and female guards and the vast majority of them all end in the same way; Charges are dropped, bonds are low, and sentences are short and unsubstantial. There is no enforcement of the laws and restrictions that make sexual contact between staff and prisoners illegal. This and the lack of substantial punishment when caught perpetuate the acceptance of rape with prisons and only allows for the rape culture within the system to continue on unchecked. Are these abuses the penal system’s idea of proactively making criminals into better citizens?

The Zimbardo-Stanford Prison Experiment involving several students from Stanford, who volunteered to enact life in a prison for a fortnight, shows just how inaccurate this idea is. A prison like environment was created and several students were selected to play the roles of guards and prisoners. What the study revealed is that the prison environment is what really causes the ‘guards’ brutality and the ‘prisoners’ actions. The study had to be cancelled early because by day six the students who were playing the guards had become so brutal and violent and the students playing the prisoners had become so submissive and dependent, the potential of sustaining genuine physical or emotional trauma was a real threat. Student prisoners become extremely dependent on their dictatorial student guards and student guards harassed student prisoners causing one such student to have to leave early because he succumbed to fits of screaming, crying and anger. It would seem that the prison system is designed only to debilitate prisoners, rather than to build them up into model citizens.

Being locked behind bars and dealing with constant abuse and rape is bound to have severe psychological effect on those within. According to Mika’il DeVeaux, a former inmate who served thirty-two years of a life sentence and wrote The Trauma of the Incarceration Experience, “no one leaves unscarred” and “people in prison experience mental deterioration and apathy, endure personality changes, and become uncertain about their identities.” Incarcerated men and women are more likely to be diagnosed with trauma related disorders such as PTSD, panic attacks, depression and paranoia, while they are still within the walls as well as once they are released. These psychiatric disturbances make it very difficult for ex-inmates to readjust to society outside the prison as they usually last long after inmates are released.

As if the mental hardships didn’t make free life difficult enough, practical life experiences become very hard to acquire due to the ex-offender label. Since 1985, the number of jobs unavailable to ex-offenders has only grown, “recently passed public housing laws now require public housing agencies and providers to deny housing to certain felons (e.g.,, drug and sex offenders),” and corrections “conditions are detrimental to successful re-integration, and restrictions [are]… deeply counterproductive.” The way ex-offenders are treated and viewed within society creates the sense that they are unimportant and of no use to society. In Darabont’s adaption of the novella, he writes in a scene when Red is discussing the release of Brooks with his friends. He claims that inside the prison Brooks was an intelligent and important man while on the outside he is no good to society, just an old, unimportant man. This unimportance is significant to the next idea King addresses: institutionalization.

Institutionalism is a serious side effect of being in prison for long term stays such as those given life sentences. According to the sociology website changingminds.org, “Institutionalization is an often-deliberate process whereby a person entering the institution is reprogrammed to accept and conform to strict controls that enables the institution to manage a large number of people with a minimum of necessary staff.” This process is often long lasting once it has been completed. Leaving the prison after years apart from society and being forced to follow a very strict and specific set of rules for all of those years, never being allowed to do anything without the permission of a guard, often leaves former inmates facing a difficult time returning to their self-reliant and managing state. They’ve lost themselves in all the years they’ve spent following an already designed and ordered schedule and many don’t know how to be a part of the world anymore. These newly released convicts often end up isolating themselves, developing mental illness, and starting or continuing substance abuse.

King and Darabont both use characters in the story to show just how devastating this process is to the inmates. King begins with Red’s release at the end of the story. Red has been in Shawshank for many, many years and, over time, has become institutionalized to such a degree that when he finally is released, he doesn’t believe he will make it in the world. The world moves too fast for him. He can’t control his bodily responses to the women around him, and he finds that his boss at the Foodway market does not like him very much because of what prison life has done to him and the other inmates. Red claims that prison “turns everyone in a position of authority into a master, and you into every master’s dog,” and so even performing the most basic human functions such as going to the bathroom, require him to ask permission or else he can’t go.

It is not much of a life to live, being psychologically incapable of performing basic bodily functions. Red often contemplates committing a crime just to be able to go back into prison where the institutionalized lifestyle has become normal and comforting to him. King shows how hard it is to truly be a better person when faced with the struggle of attempting to fit in and be comfortable in society again.

Darabont reinforces King’s derogatory statement about institutionalization when he chooses to expand on the character Brooks, who is only briefly mentioned in the novella, but who plays a large part in the film adaption of The Shawshank Redemption. When Brooks, an old man, is finally informed of his imminent release from the prison, the first thing he thinks to do is to attack his friend Heywood with the clear intention of killing him, claiming, “it’s the only way they’ll let me stay.” Brooks, having spent at least fifty years in Shawshank, does not know anything about the outside world and is immensely terrified of being sent out into it; as Red said, he is unimportant out there. He is so distraught that Red has to talk him out of murdering his friend just to stay inside the walls. Leaving the prison is the most damaging weapon to the old man’s mental health; more so than anything else one can throw at him. Darabont uses the film to clearly depict the distress he feels by including the following letter he writes to the boys still in Shawshank:

Dear Fellas.

I can’t believe how fast things move on the outside. I saw an automobile once when I was a kid, but now they’re everywhere. The world went and got itself in a big damn hurry. The parole board got me into this halfway house called the Brewer, and a job bagging groceries at the Foodway… It’s hard work. I try to keep up, but my hands hurt most of the time. I don’t think the store manager likes me very much. Sometimes after work I go to the park and feed the birds. I keep thinking Jake might just show up and say hello, but he never does. I hope wherever he is, he’s doing okay and making new friends. I have trouble sleeping at night. I have bad dreams, like I’m falling. I wake up scared. Sometimes it takes me a while to remember where I am. Maybe I should get me a gun and rob the Foodway, so they’d send me home. I could shoot the manager while I was at it, sort of like a bonus. But I guess I’m too old for that sort of nonsense anymore. I don’t like it here. I’m tired of being afraid all the time. I’ve decided not to stay. I doubt they’ll kick up any fuss. Not for an old crook like me.

P.S. Tell Heywood I’m sorry I put a knife to his throat. No hard feelings.

Through Brooks’ letter, our eyes are opened to what thoughts and emotions go through these inmates who are thrown out into the world after knowing only the institutional life for so long. Brookes, just like Red, only makes it a short time outside of those dark prison walls before he is debating murder and theft again. The world outside the walls has become far too strange and terrifying for him. He has no friends, no comfort zone, and no hope. All he is seeking is the psychological and emotional freedom from the life that has kept him caged for over half a century; but as we see in the film, when he is carving his name in the archway of his room at the Brewer, with his face still behind bars, Brooks is still imprisoned by the only way of life he has known for the last fifty plus years. The only options he believes are available to him are committing another felony or to kill himself. Brooks is devoid of hope, and with that emptiness comes the decision that the only way to handle his situation is to kill himself. He does not become better socially or psychologically as the system would have us believe happens; He merely ceases to exist except from within the memory of his friends and the readers who loved him.

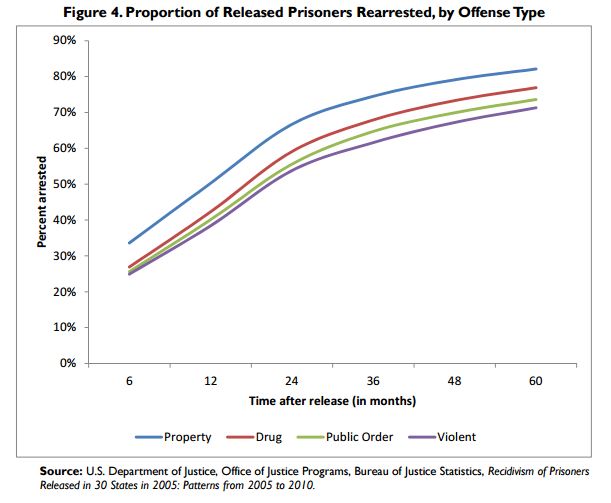

Neither Brooks nor Red are alone in their desire to return to prison. According to the research and statistics gathered by Nathan James, an analyst in crime policy, “By the end of the five year follow-up period [the period in which researches kept up with the prisoners from this study who had been released], 82.1% of released property offenders were rearrested, … 76.9% of drug offenders, 73.6% of public order offenders, and 71.3% of violent offenders [were rearrested].” Whether all of the cases in this study were examples of convicts wanting back into the system or whether some just couldn’t break the habit of committing crimes, is of little importance. The point is that quite often those who have committed a crime once before, will do it again. It would seem that philosopher George Santayana was correct; history is doomed to repeat itself.

Finally, Darabont argues the notion that prison make better people out of criminals with his inclusion of the scene where Andy and Red are in the library discussing the wardens schemes. In this scene Andy tells Red something that is of utmost importance to King’s challenge; he claims, “The funny thing is on the outside I was an honest man, straight as an arrow. I had to come to prison to be a crook.” This is where Darabont really enforces King’s impression that the penal system is actually making people criminals worse off rather than better. It is here that he makes the suggestion that rather than creating better people, prisons such as Shawshank, are in fact capable of making good citizens into criminals. Before coming into Shawshank, Andy Dufresne is a hot shot banker who is married and who hasn’t done a thing wrong in his life, except drink a little too much and fail to give his wife the attention and love she deserved before her affair. It was after he came to Shawshank prison that he became a criminal, laundering money and handling the profits from backhanded deals for the warden.

The final scenes in Darabont’s film also back up the claim that incarcerating and isolating criminals is not the best way to turn them into better citizens. However, he not only backs King up, he takes it one step further by introducing the idea that hope is the one thing that can keep a person sane and make them into a better citizen. Hope is what gets Andy out of prison; Hope is what makes Red keep his promise to Andy and go find the rock under the oak tree; Hope is what keeps Red from committing another offence or killing himself. It is what drives him to break his parole, his final crime, and go to Mexico to join Andy in making a better life for themselves.

“Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption” is a clear challenge to the American public to take a closer look at the American penal system. Steven King makes it blatantly clear that he believes that the prison system is only making convicts into worse people as well as turning decent citizens into ruffians. With rampant cases of abuse, rape and murder filling the files of the penal system’s records, it is difficult to argue his point. Frank Darabont easily takes this idea and translates it into his adaption with one clear addition, hope. Harassment, abuse and isolation will never create a better citizen, but hope is redemptive and with it a man can dream of being free and leading a better life.

…

So what do you think? Should we keep imprisoning offenders? A recent radio program explained that new legislation is retroactively lessening sentences, mostly for drug offenders, allowing some to be released early. What do you think about that? What about Capital Punishment?

What should I write about next? I’m listening.

Little Me

Sources:

DeVeaux, Mika’il. “The Trauma of the Incarceration Experience.” Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review 48.2 (2013): 257-277. Political Science Complete. Web. 24 March 2015.

Gorski, Terence T. “Post Incarceration Syndrome and Relapse.” The Addiction Web Site of Terence T. Gorski. GORSKI-CENAPS Team, n.d. Web. 24 March 2015. <http://www.tgorski.com/criminal_justice/cjs_pics_&_relapse.htm>

Hunter, Gary. “Sexual Abuse by Prison and Jail Staff Proves Persistent, Pandemic.” Prison Legal News. Prison Legal News, May 15, 2009. Web. 23 March 2015.

“Institutionalization.” Changing Minds. Changing Works, 2002-2015. Web. 4 May 2015.

James, Nathan. “Offender Reentry: Correctional Statistics, Reintegration Into The Community, And Recidivism: RL34287.” Congressional Research Service: Report (2007): 1-C-33. Risk Management Reference Center. Web. 25 Mar. 2015.

King, Steven. “Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption”. Different Seasons. New York City: Penguin Group (USA), Inc., 1982. Pages 4-56. Print.

McLeod, Saul. “Zimbardo-Stanford Prison Experiment.” Simply Psychology (2008): n. pag. Web. 4 May 2015.

Muskogee Country District Court 08.15.09. Muskogee Phoenix. Muskogee Phoenix, 14 Aug 2009. Web. 4 May 2015.

Petersilia, Joan. “Hard Time: Ex-Offenders Returning Home After Prison.” Corrections Today 67.2 (2005): 66. National Criminal Justice Reference Service Abstracts. Web. 24 Mar. 2015.

“Prisoner Abuse: How Different are U.S. Prisons?” Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch, May 14, 2004. Web. March 23, 2014.

The Shawshank Redemption. Dir. Frank Darabont. Perf. Tim Robbins, Morgan Freeman, Bob Gunton. Castle Rock Entertainment, 1994. Film.